I’m going to tell you a story, an amazing, fantastic story that you are unlikely to believe if you have any brains at all. It involves senses that you don’t have, powers beyond your abilities and travels by millions, billions that you can’t see. But the story is true, all of it, every single part of it, even the parts you will think preposterous. Those parts are the best parts.

The story is about a little bird, a warbler, Blackburnian by name, no bigger than a minute and weighing less than a whisper. The story is about the journey he makes every spring, one half of the journey he makes every year. On an April night he jumps off a branch in south America and flies into the darkness, into the unknown, unsure of anything that lies ahead. He flies from one continent to another across sea and gulf and then rides rolling ridges north to the forest of its birth. It is a leap of faith, a flight of purpose, driven by instinct, powered by impulse.

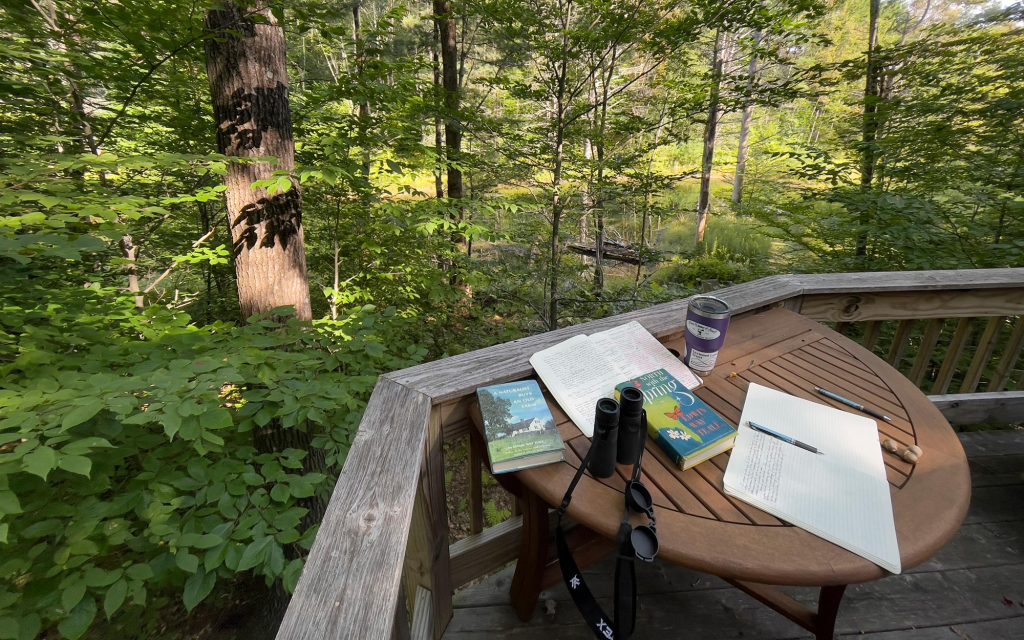

In Vermont, I see Blackburnian warblers in May in my hundred-acre woods, up in the old sugarbush, high in the treetops. He sings to announce the end of his 3000-mile journey. He sings to declare these trees, this part of the forest, his. And he sings to attract a mate who came his same way and will be arriving very soon. On this journey he travels alone, at night, with no help or protection and without the aid of any landmarks. He is guided only by the stars, the turn of the seasons and the pull of the Earth. He uses senses humans do not share, senses we can only admire and his abilities far exceed our own.

But this isn’t the most fantastic part of the story. This tiny bird not only finds its way home every Spring to the same woods, the same tree, often the same branch where it nested the year before, but it also found my way home, to my place in the world, to the place I need to be.

The story of finding home. I hope the little guy knows where he’s going.

Read samples from Finding Home by clicking on each chapter tab below.

Evelyn

A Blackburnian warbler weighs 0.3 ounces. I have no idea what 0.3 ounces is or what is 0.3 ounces but it doesn’t seem like very much to me. I do know the average American male weighs 198lbs or 3,168 ounces and, thank goodness, I’m not an average American male. The bell curve of male weights puts my weight in the fat part of the curve, but not the fat part of America; I’m on the rising side of the curve; below average, but not well below. I find being labelled as around average peculiarly comforting — it limits expectations and assumes any performance on my part will teeter on typical rather than slide into excellence. With effort, I can strive to be excellent but I have found it is far easier to lower the bar of expectation than it is to raise it. This sentiment nicely echoes my quarterly report card comments of Mrs. Rifkin, my 4th grade teacher.

The average weight of an American female, if we are being so impolite to mention, is 170 lbs. or 2,720 ounces. In case all you females are feeling superior reading this, please know that 170 lbs. is the equivalent to the weight of over 9,000 Blackburnian warblers. When the smug chuckling quiets, men should know they weigh the equivalent of 10,500 Blackburnian warblers. I check in around 10,000 Blackburnian warblers. For the record, I prefer to think of my weight in pounds and not in units of small warbler.

What is one ten thousandth of me? A toe? My nose? That funny…never mind. I need a better comparison. Something common, something every day. I head to the kitchen and open the junk drawer and paw through it looking for small items that will be forever saved but for — never used. Finding a few things, I head to my office and the garage to hunt for more odd detritus filling a small baggie with my collection. But how much does each weigh? I need a sensitive scale that measures in tenths of an ounce. Aha! I jump in the car and head into the village to our post office to see our postmaster, Evelyn.

“How have you been? I haven’t seen you in a while,” Evelyn says.

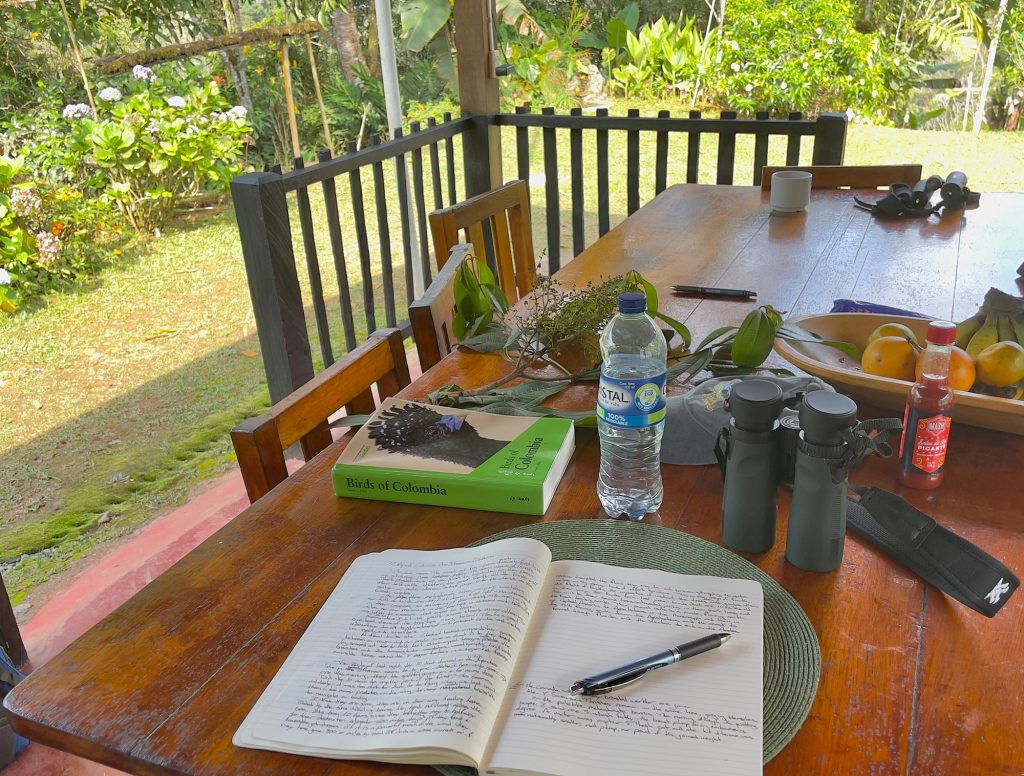

“I’ve been travelling, out of the country a lot lately.”

“Your box is full, really full. Do you even remember you have a post office box here?” Evelyn gently chides. My post office box is my second mailbox (don’t ask) and the truth is I usually don’t remember. Evelyn often must remind me to empty it. She hands me a tall pile of mail that will probably go unread, assuming I remember to take it with me.

“How can I help you?”

“I need to weigh a few things.”

“Mail? I don’t see a box. What’ve you got?”

“I have this bag of odd little things. I need to see if any of them weigh 0.3 ounces.”

“You’re not mailing any of them? Why .3 ounces?”

“That’s how much my little bird weighs.”

“You have a little bird?”

“No, I’ll try again. I’m writing about a little bird. It happens to weigh .3 ounces but I don’t know how much that is.”

“It’s .3 ounces.”

“Thank you. Have you been here all morning?”

“Not yet.”

I take a deep breath. ‘I want to know what else weighs .3 ounces.”

“Oh, why didn’t you say so? Put ‘em on the scale and we’ll see what happens.”

Evelyn is very tolerant of me and the unusual packages I bring into the post office. I once brought in a box I wanted to mail to Tasmania via the US Postal Service.

“Tasmania? Where’s that?” she asked.

“It’s an island below Australia.”

She looked at the address again, thought a bit and said, “Oh, this will never get there.”

She was right.

I start with a golf ball — 1.6 oz., then an acorn — .1 oz. “Your bird weighs three acorns,” Evelyn says, smiling. Then a wood screw — 1 oz., a key chain rubber duckie — .5oz., a bolt with nut attached — 1.1 oz., nail clippers — .6oz, two nails — .5oz. Through more trials we discover that a blackburnian warbler weighs what a house key weighs or what 3 pennies weigh, what 6 paper clips weigh, what 7 jellybeans weigh and what 2 Triscuits weigh. It also weighs a tad less than two quarters, a AAA battery, a partly used pencil and a small bite of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich (I was hungry). After a few more things — reading glasses, a light bulb, golf tees, all too heavy — I run out of things to weigh. I gather up my mess, blowing crumbs off the scale, stuff it all in my pockets and head to the door.

“Thank you!” I call out over my shoulder.

Evelyn stares at me. I stop.

“What?”

“You forgot your mail.”

Omar

He walks out of the sun-bleached forest tangled with mangroves and skinny trees as if an illusion — black rubber boots, sagging black pants, binoculars, a mini recorder across his chest. He carries a machete in a frilled leather sheath on his hip and a dirty, wilted backpack on his back. The park is empty, it has the feel of an amusement park out of season — concrete retaining wall retaining empty pools, picnic pavilions without picnics. The day is squinting hot, dry, turning the white bark of the low forest into glinting shards. It is mid-day — few birds move, fewer sing.

His smile softens the glaring day, his eyes alive with friendship and curiosity. This is Omar Munoz. He is a guide and this park and all of Colombia’s Caribbean coast is his backyard. He is shorter than I am, much slimmer, all legs and lungs. There is no space on his body to carry fat whereas on mine there is no place not to. He is a creature of the coast, part salt crust, part sun and wholly happy. I feel like a manatee next to this lean and sleek otter.

The first bird we see is a bird I had never heard of, didn’t know existed — a bronze-brown cowbird. It is high in a leafless tree, looking completely black in this sunburned forest. Omar is ecstatic, jumping around like a toddler with a new toy, whooping through a huge smile. He’s talking in machine gun Spanish — bursts of words that flash past me too fast for me understand them.

“I have not seen this bird in 7 years! I am in this forest every day and so is he but he is shier than I am, I make too much noise. What a surprise!” I try to respond in kind but my ignorance of the bird and unfamiliarity of the forest dampens my response. No worries — Omar is plenty happy for all of us.

There are other birds he points out, all in the treetops, all bright specks against a bright blue sky. We see half a dozen new birds but the only one that matters to Omar is the bronze-brown cowbird. “People come from all over the world to see this bird and for 7 years I have failed to find it for them. Today we see it first thing. This is a special day!” My ignorance has turned to appreciation, not of seeing this rare bird but of Omar’s intimate knowledge of this forest. He knows every flutter, squeak, flash, call and every tree, flower, and thorny shrub. Universities and research institutes hire Omar to do their fieldwork, his observations creating the data scientists far away fold into research papers.

Finding some shade from the unrelenting sun, we sit and drink water. Curious about how Omar got started birding I ask him to tell me.

“When I was growing up, we had birds in cages in our backyard, everyone did. We’d put a sticky goo boiled down from tree sap on branches or fence wire, wherever birds might sit and then catch them when they got stuck and keep the ones that were good singers; orioles and thrushes and yellow-hooded blackbirds were our favorites. My family had 15, maybe 20 bird cages in our backyard. Some of our neighbors would sell the birds but we just kept them in cages to hear them sing.

When I was 14, I was playing pool in the village, not doing anything wrong, when the police came in and arrested three of us on made up charges. This was a very common thing to do then. They did it to frighten us and make us scared of them. The three of us spent the night in jail behind bars. It was the first time I was ever in jail, and the last time. I hated being in jail. I hated the bars. Anywhere I looked I saw bars, even out the little window high on the back wall — bars! The next day we all had to do chores around the police station — polish their shoes, scrub the floors, clean the toilets, do laundry — all the things the police didn’t want to do.

That night we were behind bars again. I didn’t sleep. I was so scared. The next morning, they let us go and I ran back to my house. I told my father that we had to let all our birds go, to release them from jail. I didn’t want any free bird to be stuck in jail like I was, looking at the world through bars. From that day on my father and I devoted ourselves to protecting birds. We released all our birds and convinced some of our neighbors to do the same. I started walking to the little village library and reading everything I could find about birds and I started to volunteer with researchers and scientists to learn as much as I could. I still work with researchers, scientists too. And I still love birds.”

Walking back to the car I asked Omar if I could look at his binoculars. I had noticed that he had an old pair of Nikons, probably borrowed, showing wear and a lot of hard use. Local birders share their equipment here, saving money better used for their families. I have played this can-I-see-your-binos game with other people’s binoculars many times before. One hundred percent of the time the binos have either filthy eye pieces that are borderline disgusting or the prisms are way out of alignment. Either way, they need repair.

Before I look through them I ask Omar, “Do you get headaches after a day of birding?”

“Yes, I do, terrible headaches and they are getting worse. I think they are from covid I had a couple of months ago. How did you know?”

“I don’t think your headaches are from covid, Omar. I think they are from your binoculars. The prisms inside have been knocked out of alignment so your eyes are seeing two different pictures of the same bird. Your eyes, your eye muscles, must pull those different images together and after a long day those muscles get tired and you get headaches. The more out of alignment your binoculars the worse your headaches.”

I look through his binoculars and see, as I expected, they are terribly out of alignment. It’s difficult for me to focus them they are so far out of alignment.

“How long have your binoculars been like this, Omar?”

“Oh, they are not mine. I borrowed them from another guide. It’s the only pair of binos around here. We all borrow the same binoculars from the same friend.”

“Here, Omar, look through these.” I hand him my pair of binoculars. “Do you see the difference?”

He looks through them and then looks at me like he has just seen a long, long, long lost friend.

“These are incredible!”

“They are yours, Omar. Please take them. I have an extra pair.”

“No, I can’t. They are your binoculars.”

“Yes, you can. They are yours now.”

“¿En serio? No es possible. ¿Verdad?”

“Si, verdad. They are yours. You deserve them.”